Stories from Jane’s World

- Adventures - Mishaps - Critters -Life -

Dullsville

I’m standing in front of the self-checkout, merrily inserting various coins into the machine. By the look on my face, you’d think I was in Reno playing a slot machine. I couldn’t be happier, and in support of my joy, Dane digs deep into his pocket, pulls out a handful of silver and copper coins, and offers them to me, saying, “Here, knock yourself out.”

I feel like I’m at a party! I’m loads lighter from carrying less coinage, the remaining grocery bill is tiny after all the change, and I’m thrilled to hear that rumble, clink, clink, clink… Oh no, it won’t take one of my quarters. I reinsert it over and over until finally, the watchful self-checkout attendant notices and comes over.

She instructs me to give the machine time to settle down before inserting it again. She kindly refrains from saying “before inserting it for the hundredth time.” But I’m so determined to get all my coins to disappear while lowering my total grocery bill that I hardly listen.

Ding, ding, ding, all the coins have been swallowed up, and what had been a bill for over a hundred dollars of groceries for me plus tick stuff for the critters is less than five bucks! I excitedly tell Dane how little I’ve paid while pointing to my many bags.

He tries to tell me I actually paid for all of it, but I don’t listen to him either. Coins are free. They’re everywhere—in my car, in my coin purse, in a jar at home. They barely count as real money, I tell him; they're extra.

As we drive away, the joy stays with me. I ignore Dane’s gloom-and-doom lecture about no money being free.

Next, since we’re heading that way, he starts going off about the Kwik Trip cappuccino machine that he feels is out to get him. He claims one pump is not enough caramel but two pumps are too many. Dane’s life will be complete when the sweetness of his caramel mocha perfectly matches his taste buds. I listen and nod.

Then Dane tells me with a grin that he can’t wait to get back to his house. When I ask why, he says he left an overflowing container of recyclables out for collection and by the time he gets home, it’ll be empty.

Wow, I exclaim, that is exciting. I have to drive my recyclables to the dump on Wednesdays and Saturdays. I’m impressed and happy for Dane that he gets driveway service.

But then I think of the free table at our dump. On our last two visits, Dane brought home water bottles that had been left there. One leaked, but the other was a fantastic find. Not long ago, I came back to the car dragging a heavy but perfect-condition, ginormous cot-type lounge chair. Dane’s jaw dropped at the lucky score. It’s already been used for an afternoon nap on the back deck.

It dawns on me that we may qualify as dullards. There’s a fascinating group on social media called “Dull Women’s Club”—there’s also one for dull men—where people from all over the world confess to leading dull lives. (For some reason, when you introduce yourself, it’s important to state your shoe size and mention a banana.)

On our last stop today, Dane and I celebrate when we come out of Kwik Trip with a full crate of bananas that are starting to turn black, for which we paid only $4.90. When it comes nighttime and we're listing our three good things for the day, this crate of bananas tops the list.

On my list tonight I also mention getting rid of the coins that had been collecting. On Dane’s list is his recyclables getting picked up.

Not too many years ago, it seemed we weren't quite so dull, but we fall asleep tonight feeling anything but. After all, the little things that make us happy are the ones that count.

Waddle

RNIPSG

You may have played Wordle, the popular online word game that gives you 6 chances to guess a 5-letter word. When its creator, Josh Wardle, opened it to the public, the number of users jumped quickly from 90 to over 300,000. In 2021, the New York Times bought Wordle from Wardle, and now it’s played by tens of millions of people. They love the daily challenge, and it’s great brain food.

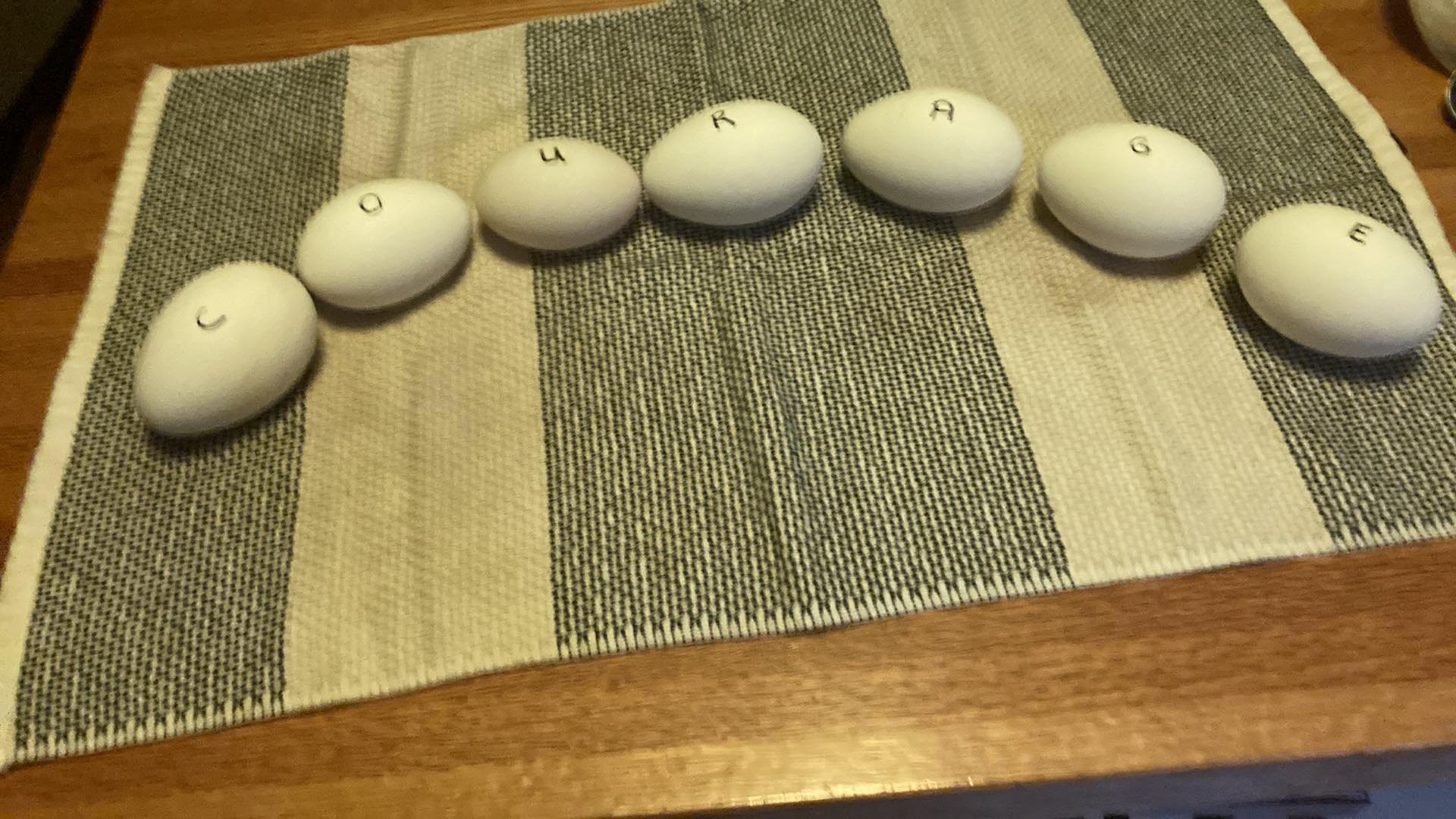

My gals at home don’t claim to know how to count, but they can spell. Springtime this year has brought out the creativity in our flock of ducks and geese.

The gals were laying their nutrient-dense eggs faster than I could eat, sell, or gift them. This springtime abundance has also enticed Willa the coyote to come and snatch some free meals. It had been a few years since she or one of her cohorts visited and wreaked havoc among the flock.

After the last dump of snow, I noticed what I thought were dog tracks near the creek by the Duck Hall. Stumped, I couldn’t figure out how my dogs had gotten out of their fenced yard. As I followed the tracks, I realized they didn’t belong to any of my dogs, who were curiously watching me from behind the fence.

The last time Willa visited and we saw her, I ran out of the house in time to stop her from snatching a poultry dinner. But now that she’s back, the flock has been grounded; they must stay inside the yard. Not fun, when they can see their beloved creek only 10 feet away.

DURNGDOE

During a recent April shower, Eleanor, the eldest goose, was holding court near the picnic table. Bess, Roz, Grace, and Beatrice listened with their long necks cocked while a few ducks lay nearby eavesdropping.

I observed them from the deck, wondering what they were up to. It was always something, I thought, like the time they discovered the slow drip from the hose and turned it into a ginormous mudhole within the minutes it took me to notice.

The following day, the sun was out and Eleanor was once again up to some type of mischief. I kept one eye open, watching the huddle down below. The back pasture was full of the huge green leaves of skunk cabbage, and the woods were dotted with spring beauties, but my mind was ruminating on three things at once: the daily Wordle, Willa the coyote, and Eleanor’s insistent squawking.

Suddenly, the flock erupted into a cacophony of loud honks and hisses. Startled, I hopped up and started down the deck, assuming Willa was nearby. But I slowed when I realized the donkeys weren’t braying nor the dogs barking.

LSOSMBOS

And that’s when Waddle was born.

Waddle!

We’d create a game by writing letters on the eggs, either duck or goose. Our egg customers would not only benefit from the protein, but instead of playing Wordle on their computers they could have their breakfast on their back decks while unscrambling the word. With 12 duck eggs in a carton and 6 goose eggs wrapped up in a bag, there was no need to stay with 5 letters. Besides, everyone knows that fowl can’t count.

PRLAI EHWRSO

These days, garter snakes are slumbering on the trails, soaking up the sun; the spring peepers are singing soprano while the bullfrogs add their bass voices; and the turtles are looking for a place to lay their eggs. Mama Crane is hunkered down in her nest and the local eagles are settled in theirs.

Soon Willa will have moved on, the flock will be back splashing and sunning in the creek, and the trillium blossoms will be gracing the countryside.

And with any luck, at least 30 wellness-aware, community-and-puzzle-loving people will be enjoying their goose egg omelets while playing Waddle.

TVATIECYRI

If You Really Knew Us…

Granddaughter, Helena, picked out Zarite (Tete) from a tank full of puppies at the Organic Valley Fair 2013

If you really knew me, you’d know that 90 percent of the follow-up emails I send say, "Whoops, here's that attachment I forgot to attach!"

You’d also know that I'm incapable of straightening out a room. If I am even inclined to do so, I empty drawers, bookshelves, or cupboards first and then go in for the deep dive. This tendency makes for a late departure whenever Dane and I have a getaway planned.

I don't like chickens. I had two chicks once and they bloodied each other with their pecking. I switched to ducks and geese and have never looked back.

Never, ever, ever will I pour a cup of hot water from my electric pot unless it has just turned off. If I get to the pot five seconds after I hear the click and see the red light go off, I turn it back on, wait for it to boil again, grab it immediately, and pour. There’s no appeal to water poured too late.

You won't catch me choosing a female dog or cat. Yes, Téte is a girl, but I didn't pick her out, my granddaughter did. Helena’s desire trumps any animal gender issues I have. On the other hand, no male ducks or geese—an all-gal flock here and proud of it.

Jane with a basket full of female ducklings and her dog, Ruben.

I can’t remember a night that I’ve gone to bed without something on my lips. Ages ago, it was a touch of Vaseline; nowadays it's avocado lip butter.

For no apparent reason, I developed a nightly obsession with popcorn during the holiday season of 2022. It could be about my dad, who used to make me popcorn and put it in a huge yellow Pyrex bowl.

Sleeping in a tent is generally easier for me than sleeping in a bed. I enjoy sleeping outdoors, so when I’m indoors I often crack open the skylight in any weather. Vacations or any getaways are often rated by what we sleep on. If a bed, Lord, please don't let it be a mattress we sink into. I can say we because Dane and I share this sleeping preference.

If you really knew Dane, you’d surmise that my Mad Hatter cleaning habits drive him batty. Especially when the car is packed, we’re ready to roll, and he discovers me wiping out the refrigerator, with all its contents scattered on the counter.

Yesterday morning when I was running late for a class, I asked Dane if he'd make me a cup of coffee when he made his. He agreed, and when I quickly started to add, "Only hot water after the...” he shouted back, "I know."

Dane is also, of course, a chicken lover.

Dane's cats are boys, but he’s had girl cats before, and he doesn't have a dog. He also doesn’t have a granddaughter who has ever said, “That one, Grandma.”

You'll never see Dane set the volume on his car radio, or any radio, to an odd number. On the other hand, I consider my need to shut off the microwave only on a number ending in zero to be completely reasonable.

Nor does he go to bed with anything on his lips other than the whisper of thankfulness for the day and hopes of sweet dreams. He is completely wacko about moisturizer too. None has ever touched his handsome face. Only recently, after I’d watched him tape his dry, cracked, and bleeding winter fingertips, did he consent to a dab of Hempz Original cream each night. Only Hempz Original, nothing else.

Unlike me, Dane has decent appetite control. If he indulges in popcorn it’s more on the scale of twice a year, not daily. (I'll refrain from commenting on his love of donuts, which I think he hid from me the first years we dated.)

If you really knew me, you'd know that one of my superpowers is to stain my shirt, jacket, or pants within moments of putting them on. I'm either dropping an olive oil–coated roasted Brussels sprout on my shirt, breaking a duck egg I'd forgotten I'd put in my jacket pocket only minutes earlier, or wiping my filthy hands on the seat of my pants. If I’m in public and someone points out my stained clothing, I act surprised: "Oh, gosh, thanks!"

Never, ever, ever would Dane be caught dead with a stain on his clothes. He is meticulous and stain-free. Once we were driving down the road and he braked so fast I thought I had whiplash. Before I could even open my eyes, he’d hopped out the driver's door, opened the back door, and grabbed a pair of cargo shorts identical to the ones he was wearing. As I watched, now wide-eyed, he peeled off the pants he was wearing, faster than my pig Louisa could inhale a banana, slipped on the new ones, hopped back in, and resumed driving.

When I asked him what the hell had just happened, he nonchalantly said, "Had a stain." To which I quipped, "Good thing this wasn't a first date."

Lastly—and indeed I saved this for last because I could barely bring myself to type this—I’ve never used the initialism LOL in a column, an email, a conversation, or any social media post. It was hard for me even to type it here, but because I prefaced it with the word initialism, I feel better about it.

If you really knew us and we really knew you, you’d know that we all have odd behaviors. Yet here we all are, in this crazy, mixed-up, wonderful world, limping along together. Laughing out loud!

Dane with his boy, Spike.

I See You

Greg around 6 years after watching Romper Room

Romper, bomper, stomper, boo.

Tell me, tell me, tell me, do.

Magic Mirror, tell me today,

did all my friends have fun at play?

Chances are high that if you were a preschooler between 1963 and 1974, you remember watching Romper Room. If so, did you sit in front of the TV set at the end of the show, waiting for the cheery teacher, Miss Nancy, to see you and call your name as she looked through her Magic Mirror?

Greg did.

When I lead my Zoom fitness classes each morning, the little boxes on my computer monitor remind me of the game show Hollywood Squares. Unlike Hollywood Squares, though, most of the boxes at the top of my screen are dark, with only a name and no face or body. Most people leave their cameras off. I suspect they may want to keep their PJs on.

But on a recent day, there was Greg! Dressed for exercise, he appeared eager and was soon following along fabulously, working hard. Delighted, I called out, “I see you, Greg!”

Later that morning I received this email from him:

“You've said a couple of times that you can see me during class. That gave me a flashback to about sixty years ago when I was a little kid and I'd watch a children's program called Romper Room. They would sing songs, read stories, etc. At the show's closing, the host would hold up her Magic Mirror (basically an empty mirror frame), look through it at the camera, and call out the names of the children she ‘saw’ (“I see Jimmy, and there's Mary…”). Every time, I'd get right up in front of the TV, hoping she'd see me, but she never did. So you saying you could see me made my inner child very happy.”

It wasn’t even noon yet and I was delighted for the second time in one day. What a heartfelt memory Greg had shared.

Imagine four-year-old Greg, sitting in his spacious 1960s living room in front of the bulky black-and-white TV set, eagerly waiting as Miss Nancy brings out her Magic Mirror. I can picture the young boy, his face a few feet from the TV set, waving and wiggling with anticipation, hoping that today she’ll see him and say his name. And when, again, she doesn’t, imagine his disappointment.

How crushing to be overlooked again and again. How careless of an adult to set up this disappointment. Who would do that to someone?

We all do. I have. And I’ve had it done to me.

Miss Davenport, my second-grade teacher, had that effect on me. She never looked at me, said my name, or called on me the whole year. I still think of her as my worst teacher ever, especially when the Scholastic book catalogs came. Those colorful pamphlets displayed all kinds of children’s books that we could order, if our parents let us. I lived through the torture of trying to sit still, hoping that this time Miss Davenport would call on me to hand them out, like handing out candy to my friends. But she never did.

When I mentioned Greg’s Romper Room experience to others, I discovered that my friends Jamee and Phyllis were never “seen” by Miss Nancy either. As I dug deeper, it became apparent that Miss Nancy, or other important figures, left many children feeling like they didn’t matter, that they were invisible. Some even cried. Dane says he’s glad he didn’t have a TV until he was well past Romper Room age—he knows he never would have heard his name spoken.

Miss Nancy, or her producers and writers, had to have known that there were millions of kids waiting for her to see them and say their names. How easy it would have been to hold up her mirror, lean into the camera, and say, “I see you. I hope you have a wonderful day full of play.” A more generic yet sincere greeting wouldn’t have left some kids out.

All of this reminds me of the time Dane and I took kayak lessons at a popular place in Madison. Dane was new to the sport, and although I’d been kayaking in Milwaukee for years in my yellow Swifty kayak with my yellow Lab, Riley, I'd had no official training, so we were both excited to take the workshop. Dane had already purchased his boat at Canoecopia, a large paddle sports event in Madison, and I had upgraded from my Swifty to a spiffy orange Dagger. Neither boat was costly, but they worked great. Sadly, it turned out to be a nightmare. There was only one other couple plus the instructor. The instructor took to the other couple with their fancy sea kayaks and all but ignored us. It was a horrible experience, especially for Dane, since it was his first lesson.

Children might believe in magic mirrors, but we know better. Being seen is the real magic to make someone feel good about themselves. Let's make an effort to start seeing and appreciating each other better. You just might bring some long-overdue joy to someone's inner child.

Greg sixty + years later after watching Romper Room

Musings on Life & Death

Everyone is dying.

I’m dying.

You’re dying.

We all die.

When and how we will die is a mystery, but we know we will.

Cancer, car accident, lightning strike, falling off a cliff, old age...

I’ve read that it’s good to think about dying.

Not every minute, every day. That would be too much.

But sometimes.

It helps us to live better, according to scientists and psychologists, not to mention most spiritual traditions.

Psychology refers to the concept of mortality salience, meaning the awareness that we will die, which can raise our sense of self-worth, encourage us to be less money oriented, and might even make us funnier.

There are new social movements such as Death Cafes, where people get together and talk openly about dying, based on this research.

Sounds like a hoot!

But it seems to make sense.

If we talk about dying, inevitably we’ll talk about life.

I’m big on living while we can, making the most of each day.

Living fully while we can might mean that we’d appreciate our eyes more, opening each morning.

Or feel joyful about witnessing a magnificent mackerel sky at sunset.

Perhaps it means a long, lazy Saturday nap in the sunshine on the back porch.

Or an equally long, slow walk with a friend you haven't seen in a while.

It’s a stretch for me to see how thinking about death will raise my sense of self-worth.

In fact, it seems to increase my neuroses.

I have a bad habit of fearing my loved ones have died when they haven't.

Maybe they have a cold, didn’t pick up their phone, or weren't at a local event where I thought I’d see them.

Dane tells me to stop killing him off before he dies.

We both find this funny, but not everyone does.

Not when I’m begging someone to come home from vacation because I don’t want them to die while they’re gone.

As for being less money oriented, how much less do they mean?

Money comes. Money goes.

We make money. We pay bills. If we’re smart we save money.

But I’ve never been that smart.

I grew up hearing we should save for a rainy day.

Yet rainy days for me are days where I try talking Dane into getting matching tattoos…because it’s raining, honey, and what else can we do?

As for being funnier, my friend Paige, on a Ride Across Wisconsin bike trip, once told me, “You’re not funny. I am.”

And she had a point.

She is funny. I wonder if she ever thinks about dying?

So I’m not yet clear on how thinking about dying will help me, but I do it.

I’ve been trying for years to get Dane to sit with me and fill out “My Final Wishes,” a booklet from the Threshold Care Circle.

It makes sense.

Recently, we received two copies as an engagement gift from a smart friend who is kind and whose husband died unexpectedly.

She knows.

It also makes sense to clean out your attics, basements, and storage sheds asap.

Get rid of the crap or you’ll be leaving that horrendous job for the people you love best.

Maybe I’m thinking more about death these days because so many friends have died, or their parents have, or their spouses, or their brother or sister.

Wake up calls come daily.

Someone suddenly gets ill and their life spirals downward, when the day before, they were harvesting their garden.

Nope, we don’t know…

Death isn’t choosy.

Young and old people die.

Healthy and fit people do too.

People who sit and read all day die, as well as people who run marathons.

It may be healthy to think about dying, but I suspect it’s equally important to focus on living.

And ultimately, isn't this the point? By contemplating our death, to become more aware of how precious this life is.

To be grateful when our eyes open.

To give thanks for that mackerel sky.

And to fully grasp that life may be short, but thankfully, it’s also wide.

Birth of a Business

Exercising outdoors during the pandemic

The conception of Fitness Choices happened after a hallway conversation at Vernon Memorial Hospital, where I was working as a fitness instructor at the Heart Center. I was spitting mad, and Janet, who worked in the marketing department, was listening. I’d given the job everything I had: I’d helped install a better tracking system, overseen the development of their racquetball court and its use, implemented and led new fitness classes, helped get and promote much-needed equipment, and reworked new members' orientation process to include three initial training sessions. My rant was about my recent performance review in which I’d excelled, only to get a lousy nickel raise. I was furious and also broke.

As I drove home, still fuming, I decided to start my own business. I would offer exercise classes at schools, churches, and community centers. My goal would be to make the benefits of participating in a regular exercise class accessible to more people.

The actual birth of Fitness Choices was more challenging. Living off the grid meant no telephone or computer, so I rented a post office box in Westby and advertised in the Broadcaster. There wasn’t any other way to communicate, short of driving my beater car around and shouting out the window. I placed the ads and waited.

Eventually, my friend Pat Martin and I fixed up a room above the Embroidery & More shop in Westby. We dragged over a desk her husband, Roger, made for me out of an old door, along with a ton of fitness books and a horde of fitness paraphernalia I’d been storing in a rental locker. Once I got a phone installed I was able to add the number to the business card–sized ads in the paper. Then we hooked up an answering machine to capture messages from anyone interested.

The first classes were held in the dance studio in that same building. The stairs leading up to it were not only steep but in poor shape. My biggest worry was that someone would fall before they even made it to the class.

Finally, during the teen years of Fitness Choices, word of mouth helped and I held classes in a dozen places: the libraries at the Kickapoo and Viroqua high schools, on the stage at the La Farge school and also at the town’s community center, in the hallway of Brookwood High School in Ontario and later in their old community center, in a church basement in Genoa, in the backroom of the Gay Mills Co-op and later in their large new community building, in Organic Valley’s cafeteria, at the Viroqua Athletic Club, in the “vanilla church” in Westby, in the Viola Village Hall, and at the Church of Christ in Viroqua.

For years I also taught water aerobics at Super 8 and in the pool at Kickapoo High School. Both of those classes were my favorites since I was still living off the grid. Taking a shower after teaching was a bonus! But driving around several counties in all kinds of weather, in undependable cars, dragging my equipment from place to place, was stressful.

When COVID came I thought it would be the end of Fitness Choices, but soon I was leading classes at the outdoor pavilion at the VFW Post. Being outside was great until we had to start wearing hats and mittens. Besides, by then we were being told to stay at home.

Once again, I found myself fretting and fuming and talking to Janet, this time from my home (no longer off-grid), not hiding in a hallway. I was bellyaching to her about clients wanting me to teach online. I’d never heard of such a thing and I wasn’t too keen on it. Janet loved the idea and, as usual, encouraged me to try.

I went through some growing pains learning how to use Zoom. My screeching birds, Benny and Joon, were a noisy distraction; the dogs took up what little space I had to teach in; and the cats were ever present, either climbing on my back, chasing each other on the stairs, fighting, or even, one time, coughing up a hairball.

Today, it’s been 22 years. Fitness Choices has come of age, and we reach more people than ever. Janet attends classes with her husband, Mark, whether they’re in their rural La Farge home or vacationing in Mexico. My neighbor Pat, who had stopped coming because of the time it took to drive back and forth to Viroqua, now attends year-round, even when she’s wintering in Arizona. Her friend Linda, who lives in New Berlin, joins in. One longtime participant, who'll be spending two months in Spain, reported that she’ll be Zooming in!

After class, some of us go to work, others get together for a walk, and some go for coffee with a friend or participate in local events. We understand and value the importance of socializing, and we often chat before or after class, but we take our morning exercise seriously, no differently than brushing our teeth or eating breakfast.

Lillie, whom I met while leading classes at the Heart Center, now joins us from her Oklahoma home. She moved there to be closer to her family as she ages. At age 98, Lillie still participates in classes twice weekly and has become a role model for all of us.

The goal of reaching more people came about unexpectedly. And maybe the lesson was going with the flow, or not giving up, or maybe it was listening to Janet. But whatever the case, Fitness Choices: For the Health of It looks forward to another 22 years!

Water aerobics at Kickapoo High School

People Are Asking

There haven’t been any Dane and Jane eruptions of volcanic size or that register on the Richter scale. I’m not certain why this seems to disappoint some people.

I shared my puzzlement with Dane, and we discussed it. We’re not certain, but the hitch seems to be in the fact that we've been living together for almost six months and haven't melted down, thrown a vase, or killed each other.

“How’s it going with Dane and you living together?”

“Good! We’ve always wanted to be able to take care of each other if something ever happened, and something did happen. We'd been discussing this very thing only days before Dane’s heart attacks.”

“But how’s it really going?”

“Good! Dane is committed to getting better so he can work again in May, and I’m helping him.”

“Yes, but I know you like being alone, and you always say that Dane enjoys his solitude too.”

“Yep. I go to my office to work, write, and often meet friends for a long hike. I regularly take Dane to his house for a day or two to visit his cats, and he often goes into the spare bedroom to read a book.”

“But how’s it really going?”

Before this period of cohabitation, we’d often explained to friends that we have two separate homes because we met as adults and each of us already had a home. To us, this is straightforward. To others, it seems to indicate we can’t live together.

But why wouldn’t we be able to live together? Perhaps because I never seem to remember basic things, such as where the scissors drawer is after using the scissors to open a bag of dog food, and Dane would never be able to live with my forgetfulness.

Or maybe because I go crazy when Dane is silently (except for his chewing) standing behind me while I’m writing. So I’m committed to two houses and never anything less.

But the honest-to-Pete truth is that we do well together. I feel kind of odd, like we’re letting people down, but Dane doesn’t. Dane thinks it’s funny—which makes me see the humor also.

Recently, I started making up different answers to the big question of how Dane and I are managing while living together during his recovery.

I could say, “Yesterday, I ate my dinner sitting on the toilet with the door closed. It’s the only room in the house with a door, and I need my alone time.”

Dane could try this approach: “My brother takes me grocery shopping. I load up on all sorts of crap Jane won’t let me eat. When Jane is working or in the shower, I sneak down to the basement to eat the forbidden treats.”

By far the most difficult day for both of us in these past months was the day Dane had to go back to Gundersen to get stents put in. It turned into horrendous hours of waiting, making both of us anxious and crabby. We were exhausted, but we thought Dane would miraculously feel 100 percent better the following day. When he didn’t, that was the last straw—we both crashed.

But we didn’t yell or scream at each other. I walked up the hill to blow off steam and ranted to a girlfriend on the phone, and Dane recovered by dozing off and on.

It’s been over four weeks since Dane had an internal defibrillator put in, and he can now safely lift his left arm over his head. Without fail, he goes for a walk every day, watches his diet, and takes his medications meticulously.

April 23 is the day he’s waiting for. I’ll drive him to the DMV office, where he’ll get his driver's license reinstated and be the happiest man on earth! Not because he can’t stand living with me one day longer, or I with him, but because he’ll have his independence back. The ability to come and go as he pleases. And, most importantly, he’ll be able to work again when his seasonal job starts in May.

So, to answer the big question, we’re good! More than good. We’ve learned that we can live together under one roof, for better or worse. But now it’s going to take time for both of us to get used to not living together!

What Mom Said

“Janie, sit up straight.”

“Cross your legs.”

“Eat your vegetables!”

Parental tapes run through my head whenever I say, think, or do something Mom would have said, thought, or done. Maybe this happens to you, too.

With distance (and age!) we begin to understand how we may have driven our parents bonkers and how they drove us mad. At last, we can decide which bits of parental advice we’ll hang on to, and which ones we’ll shout “Good riddance!” to.

Because I was born with misaligned feet (turned in toward each other as if they were praying), I wore Forrest Gump–like metal braces even before I could walk, followed by years of corrective saddle shoes. I’m not sure if this was part of the reason for the posture concern or if Dad's being in the military was. Nonetheless, there was always a strong emphasis on sitting up straight and crossing my legs. “Be a lady,” Mom would hiss.

As for eating vegetables—the horrors! To say I was a picky eater is like saying McDonald's has a hamburger on its menu. To be clear, it wasn’t only vegetables I despised. The list was lengthy, starting with white milk, any type of cheese other than the highly processed orange kind individually wrapped in plastic, and, Lord help me, bread crusts.

Did our parents fear we wouldn’t be strong enough to climb the rope in gym class, our brains wouldn’t have enough fuel to concentrate in school, or that one morning we’d wake up and be nothing but skin and bones if we didn’t eat what they put in front of us?

Today, old enough to question my own eating habits, I replay those childhood memories of dinnertime: Sitting alone in the kitchen at the round maple table, shoving buttered (no, it didn’t help) veggies from one side of the plate to the other like a children’s game: “Red Rover, Red Rover, let Mr. Green Beans come over.” Watching Mom out of the corner of my eye while trying to scooch kernels of slippery corn into my napkin without her catching me. Or slipping those now-cold, mushy trees of broccoli to Kelly, our Dalmatian, who would be faithfully waiting under the table.

“Posture Aware” is an idea for a button I may make and start handing out. Harping on posture is something I’m guilty of, as much as if not more than Mom. As I age, I’m even more conscious of drooping shoulders, a forward head tilt, and holding my book at eye level. Preaching about exercises like cat/cow, chest-stretching work, and back strengthening seems to be my life’s calling. Pressing the back of my head against the headrest in the car to lengthen my neck has become as reflexive as putting on my seat belt.

Within the past few years, I, Jane Ann Marie Schmidt, began loving vegetables. When I claim this out loud, I think of Mom, who, when she could no longer drive, was upset because she couldn’t go out and get her favorite foods: hamburgers and vanilla malts. Unlike her, I’m now hooked on vegetables, whether cooked (no butter, please) or raw in salads. I swear they are a cure-all for the aches and pains of age, just as ditching sugar and flour were. My parents would be proud!

As for crossing my legs, no way! Habitual leg crossing can cause all sorts of unwanted issues, such as greater trochanteric pain syndrome, less circulation (causing havoc with your veins), scoliosis, or a shortening or weakening in muscle length and strength. Whether my hip difficulties have been the result of too much early emphasis on my feet (and ignoring how that affected my hips), or years of hungry spirochetes from Lyme disease gnawing on them, I will never know. But I do know that I try hard not to make matters worse by crossing my legs.

Another parental phrase I recall from childhood is, “Remember to say please and thank you.” To this day, these remain some of my favorite words. Thank you has become a prayer I whisper when, after winter, I notice the cranes in the field, discover the toads croaking in the creek, or see an eagle swoop down from a tree and fly alongside the car as if we were racing.

Reflecting on those parental tapes brings a smile to my face. I’ll continue to be aware of my posture, enjoy the many benefits of eating vegetables, and speak politely, but I won’t be crossing my legs.

Besides, crossing my legs doesn't make me a lady—but saying please and thank you just might!

A New Chance at Life

Nikki and her son, Connor Jones

Nikki was lying on a hospital bed next to her 19-year-old son, surrounded by tubes, machines, nurses, and the deafening sound of her heart breaking when he was pronounced brain dead.

She asked if he could be an organ donor.

Thanks to Nikki’s generous question, Connor Jones’s pancreas, liver, heart, lungs, and kidneys gave five people a new lease on life, and his corneas restored eyesight to two more. Writing about their story last year inspired me.

I was already registered to be an organ donor upon death. But after learning more about the thousands of people waiting, and often dying while waiting, I decided to step up and apply to be a living kidney donor. After all, I figured, I have two healthy kidneys and only need one.

First came an email from UW Health, acknowledging my request to be a donor. Then Rich, a kidney donor mentor, called to share his experience and answer my endless questions. Soon Melissa Schafer, UW Health’s transplant coordinator, was reaching out via email and phone.

The live donor process is impressively thorough. Everything in your current and past health history and your family’s health history is examined. I was almost turned down because of a long-ago cervical cancer scare, but was reinstated when they learned I’d had a hysterectomy with no follow-up treatments required.

My age (66 time of donation) and other factors—nonsmoker, nondrinker, with normal blood pressure, great cholesterol numbers, and not on any medications—were helpful. Being physically active and having made significant dietary changes over the past few years was also beneficial.

Eventually, I was scheduled for an all-day series of tests in Madison. Meanwhile, my friend Joan had read my column about Connor’s gifts of life and mentioned that her nephew-by-marriage, Tom, needed a kidney. Tom is in his early 30s, has three young children, and loves fishing and nature. I gave Tom’s full name to Melissa and she made the contact. Tom would be my potential kidney recipient, and Joan became my cheerleader throughout the process.

On Valentine’s Day, which is National Donor Day, Dane and I arrived at UW Health at 7 a.m., carrying a jug of 24 hours’ worth of urine in my favorite Grand Canyon souvenir bag. Dane went off to find the cafeteria while I checked into the Transplant Center.

For over 55 years, UW Health has led the nation in serving transplant patients, both adults and children, and living and deceased organ donors. I was in expert hands.

My long day of testing started with handing over my prized bag of urine (the bag had to be tossed because I hadn’t screwed the lid on tight enough!) and having 15 vials of blood drawn.

After the blood draw and a complimentary breakfast, I met with a nutritionist who assured me there were no concerns with my A1c (diabetes screen), lipid panel, or blood pressure. She declared me a “good nutritional status for donation.”

The 10 hours of tests and interviews continued with a chest x-ray and an electrocardiogram. Dr. Wang, one of the kidney surgeons, reviewed my past medical history, surgical history, social determinants of health, current vitals, and physical exam, and counseled me on the donation process and its potential risks. Her notes concluded, “I think she may be a suitable candidate for kidney donation.”

When I finished answering the social worker’s questions about my support systems and my living and work arrangements, I was getting fatigued. She summed up in her notes that “patient is a low-to moderate-risk psychosocial candidate for living donation.”

Next, I spent an hour with Dr. Swanson, who was pleased with my metabolic and electrocardiogram test results. Finally, I met Melissa in person for the first time. She walked me to radiology for my last test of the day, a CAT scan.

Because I was asked by everyone I met with why I wanted to donate a kidney, I was able to say Connor Jones with a smile many times throughout the day.

When Dane and I left the hospital at last, I was starving and thirsty! Dane was content—he’d finished his book while waiting for me.

My case was to be reviewed at their next Wednesday meeting, and on Friday Melissa would be calling me with the good news.

By now we knew, because of my age, I wouldn’t be a direct candidate for Tom, but giving my kidney to someone else meant Tom would move up on the waiting list, a huge deal to him and his family.

On Friday, Melissa called. I’d been turned down to be a donor.

In reviewing my CAT scan, Dr. Swanson noticed one kidney was larger and one smaller. Both had cysts, and so did my liver. I was referred to a nephrologist at Gunderson Health in La Crosse, where I learned I have stage 2 chronic polycystic kidney disease (PKD). Not a biggy, because there are 5 stages. Our guess is my dad was the carrier. He died at 53 from a brain aneurysm, which can result from PKD. My next step was a brain and neck scan—no signs of an aneurysm—and I'm scheduled for a genetic counseling evaluation.

So now I need you to step up and become a donor. You’ll have the best donor team to work with and the best testing imaginable. More important, you’ll give someone like Tom the gift of seeing his children grow and taking them fishing. For more information on being a donor or sending a donation, go here: www.uwhealth.org/transplant

Make sure to tell them Connor Jones sent you.

Benny & Joon: Two Birds Are Better Than One

“Watch it, I’m sitting below you.”

“Then move. Not my problem.”

Often, Benny and Joon sounded like squabbling siblings. I could just imagine how their chirps and churrs would come across in English.

“Don’t touch me like that.”

“I didn’t even touch you.”

More often, they sounded like star-crossed lovers while poking their beaks at each other quicker than a jackhammer: Mwah, mwah. Smack, smack.

I thought of our pair of parakeets—green Benny and blue Joon—as “budgies for life.” They’d been rescued over 10 years earlier from a community services client in Richland Center who couldn’t keep them in her apartment any longer.

The day I drove home with the pair had been hot and sunny. I was expecting Dane soon and knew he’d be tired from a long sweaty workday, so dinner was ready. Benny and Joon’s cage was on a table in the living room, overlooking the back deck and yard. I’d opened the window a few inches so they’d have fresh air. They seemed content, not too talkative, as they took in their new surroundings.

After Dane washed his hands, I ushered him outside for a lovely dinner under the shade of an umbrella on the back deck. The ducks and geese were roaming the yard below, quacking and squawking as usual. The dogs, also tired from the heat, were lying near our legs.

Benny and Joon must have finished settling in, because they started talking—squabbling! I hadn’t mentioned them to Dane yet, who kept looking around, puzzled. “What’s that noise?’

“The birds,” I answered, and he looked toward the yard and the flock, shaking his head. Finally, he stood up, looked in the window, and said, “Parakeets?!”

Soon Benny and Joon’s racket became a normal part of the household. If they were quiet, we’d check on them to see why.

One day I set a pot on the stove with oil and popcorn and went outside to do chores. When I came back in, the house was full of smoke, and flames shot out from the burner. I quickly opened windows and fanned out the house, but I heard a thunk. In the morning, I discovered it was Joon. The smoke had killed her.

Benny was fine but lonely. Off to La Crosse I went and came home with another blue female, whom we dubbed Joon II.

Benny and Joon II enjoyed short showers whenever I cleaned their cage. They had every toy made for parakeets—so many that we rotated them to make their life more interesting.

One of their toys was a little basketball hoop with a ball on a chain. Benny turned out to be a pro basketball player. He once sank 24 baskets in less than two minutes, with Joon II standing close by, cheering him on.

A few years later, Joon II unexpectedly died. This time Dane and I both went to Petco and drove straight home with Joon III. Benny was thrilled and started yakking at Joon III almost immediately.

It wasn’t until a year ago that my critter sitter noticed Benny’s beak was overly long. I’m nearly blind close up without my glasses and hadn’t noticed. Benny went to the vet, the vet trimmed his beak, and life went on, with Benny and Joon III scolding, kissing, and more chipper than ever.

But Benny’s beak kept growing back as fast as the vet cut it, until the third visit, when she confirmed that the excessive growth was a result of liver disease. There wasn’t anything to be done, and soon we started trimming Benny's beak ourselves instead of scaring him with a vet visit.

Recently, Dane wasn’t feeling up to catching and holding Benny, so my friend Carol said she’d help. After I showed her a picture of how to hold Benny, she rolled up her sleeves and got busy. Just as she was about to put her hand in the cage, I asked, “Would you rather do the trimming?”

“Nope.”

Soon Carol, a real parakeet wrangler, had Benny in a secure hold. It took only my reader glasses and a quick snip, and soon Benny was telling Joon III all about it.

Looking at Joon III, I wondered out loud if her beak might need trimming too. Carol looked, Dane looked, and the consensus was, “Maybe a little.”

Again I asked Carol: hold or trim? Choosing again to be the holder, she prepared to catch Joon III and reached into the cage just I remarked that she was a real biter. Immediately Carol shrieked a cuss word louder than Benny and Joon’s combined screeching.

“She bit me $#@& hard!”

“I know, and she hangs on too!” I exclaimed.

Carol gave me the stink eye and screamed, “Ouch, @$&5#, she’s biting me again!”

“Hang on, Carol, I’m ready to cut her beak.”

“Oh my god, it hurts. Aacckk, she got me again! @!#$$!”

I empathized, “Yes, she’s got one heck of a strong beak.” Carol glared at me as she held Joon out for me to cut her beak.

Dane was rolling on the floor with laughter, but I was still empathizing when I said, “Nope, her beak looks good. Just put her back in the cage.”

Then I erupted in laughter at Carol's horrified face as she held up her bright red finger.

To be continued…

The Slow Adventure

“Huh—when I cleaned out the snail house, I had six snails. Now I only see five. I wonder where the other one is hiding.”

Dane sighs. He gets exhausted when I go on about my pet gastropods, whom I faithfully mist morning and night and continually watch. Garden snails, classified as mollusks, are nocturnal, and that’s perfect for me. I often get up during the night, which is a great time to spy on them.

Putting my ear into the aquarium when they're perched on a celery stalk is delightful. Chop, chop, chomp, go their tiny, razor-sharp teeth. And I adore watching them in their bathtub, which also doubles as their drinking dish. They stretch themselves out as if they’re sunbathing, and dip their heads in the water like they’re trying to cool off.

I started my aquarium of garden snails with Flo and Griff, and now I have “Flos and Griffs.” It was too challenging to keep adding names. When I talk to them, they all stop what they’re doing—sliding, sticking to the glass, getting some calcium, taking a bath, or eating—and strain their adorable bodies toward my voice. Their eyes (atop their eyestalks) can see me, but since they don’t have ears, they feel the vibrations of my voice inside their glass home.

“Hey, Dane, there’s one big one that has a crease in her shell. Could she have eaten one of the other snails? A neighbor told me she thinks they absorb the babies. And we used to have tons of babies.”

“Absorb babies?! What does that mean?”

“I’m guessing it means eating each other.”

Dane sighs again and leaves me to my ruminations. I start to question my memory. Could I have miscounted and had only five? When I slice a cucumber and set it in their feeding bowl, I start to poke around. Maybe one of the snails is under the dirt, laying eggs.

Technically, since they are hermaphrodites, both Flos and Griffs can have babies, producing up to six batches of eggs in a year. We’ve seen at least three big batches in the past two years. Each time, I’ve come downstairs, stopped to say, “Good morning, snails,” and then exclaimed loudly, “Babies!”

After mating, each snail can lay around 80 eggs in a hole in the soil. They’ll hatch two weeks later. Seeing as I started with two snails and now have six—okay, five—large snails and no babies, maybe some absorbing is going on.

After doing a bit of research, we discover that snails don’t eat other snails (I sigh in relief), but they may scrape the shells of others to get calcium. Exploring a little further, I learn that egg cannibalism can happen: the first snails hatched in a clutch may eat other eggs. It’s been awhile since I cleaned their aquarium, and I’m still counting snails when Dane comes sleepy-eyed down the stairs. He stops when he sees what I’m doing.

“Come here and count, please,” I ask him. “How many snails do you see?” With a sigh, he looks at the aquarium for a split second, says, “Five,” and shuffles off to get his cup of tea.

A few days later, I'm hustling, preparing for my friend Bonnie to help me paint some walls. Every knickknack needs to be moved out of the living room. I start to fill other surfaces—the kitchen island, the top of Dane’s desk, and the counters—and soon run out of empty spaces. I decide to move the dish rack to make more room when I yelp, “Flo...Griff…snail!”

No one is here to share my excitement as I scoop up the snail from its hiding place, quickly mist it, grab a handful of lettuce from the fridge, and set the snail on the lettuce. There were six snails after all!

Dane is at his house, visiting his cats, not wanting to get in the way of the cleaning and painting, so I call him. “Six!” I exclaim. “The sixth snail was living under the dish rack!”

Dane doesn’t respond, so I repeat myself and tell him the snail must have gotten out when I cleaned their house. Because they're nocturnal, we didn’t see it. I figured it was climbing into the sink at night and eating whatever veggies had gotten stuck in the strainer, then climbing back out and sleeping peacefully under my clean dishes. The dishes go into the rack wet, so he/she was even getting misted.

It’s a good, good day here. All day long I’m silently chanting, Six, I have six healthy snails! As for Flo or Griff or whoever it was that was living off sink leftovers, they're fine. Better than fine—they had an adventure! Within a minute of setting them on the lettuce, I could hear them healthily rasping away: chop, chop, chomp.

In Memory of Barbara

Barbara; top row, far right, with the pink dumbells, green shirt, and beautiful smile.

Every so often we meet someone who inspires us by the generous way they live. Barbara Martinez was like that for me.

I first met Barbara and her husband, Ed, at a fundraising event for the Family & Children’s Center that took place in Viroqua at what was then called The Ark (now The Commons). Dane and I sat at a long table with our bowls of soup and greeted our tablemates. It turned out that Barbara and Ed knew Roger and Pat Martin, my neighbors at the time, and a lively, lovely conversation ensued.

I felt a natural connection with Barbara, who was a loyal advocate for the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and The Other Door. She was also interested in wellness and soon began attending a fitness class I taught at the Viroqua Church of Christ.

Barbara was leading the Vernon County chapter of NAMI, and we decided to hold a fundraiser where I’d lead a fitness class and donate the proceeds. Barbara was instrumental in organizing the event. Unsurprisingly, the room was full that evening, and a gorgeous spread of healthy snacks was offered after.

Barbara chose the same place to sit for each exercise class: over to the right, midway back, aisle seat. From the get-go, I was impressed with her dedication. If she needed to miss a class due to travel or an appointment, she told me ahead of time—and those times were rare.

Often, we’d have a two-minute conversation before or after class, like the time she excitedly told me about her upcoming visit to see her son. I knew from the start that Barbara was a giver, a caretaker. One gal in class was going through cancer treatment, and Barbara made herself available for rides when needed. Another time, Barbara walked in with a new lady and introduced her to me. Bonnie was also in cancer treatment, and Barbara had told her about the class and started bringing her.

I learned that Barbara didn’t like it when I brought music and the class got a bit too dancey. She liked her exercises to be straightforward, easy to follow, and efficient. When COVID came, she started attending the complimentary outdoor classes offered at the VFW post. She always wore a mask and somehow managed to find that same place—off to the right, midway back, next to the aisle.

When, during the stay-at-home period of COVID, we transitioned to offering online classes, Barbara was a huge support. From day one, she signed up for and attended every class she was able to. It wasn’t unusual to get an email from her, thanking me for class and telling me how her life had benefited from it. Sometimes Dane and I would walk at Sidie Hollow after class, and Barbara and Ed would often be there, finishing up a walk themselves!

When Ed had a medical challenge, Barbara emailed me and shared the news. She was upbeat, dedicated, and positive about her husband's recovery, and sure enough, the next time we had a chance to talk in the Co-op, Ed was recovering and doing well.

About a month ago, Barbara missed a class, and I noticed. Then she missed another class, and I sent her an email. When Barbara didn’t answer, I began to worry, because it was so uncharacteristic of her. I reached out to their daughter, Sara, sent private messages on social media, and eventually found out she was having a medical crisis.

Ed kept us updated while caring for Barbara and navigating the medical world along with Sara’s guidance as a nurse. Many friends sent well wishes and prayers, and candles were lit in her honor. Sadly, it wasn’t long before Ed sent another email telling us that Barbara had passed peacefully from brain cancer.

Barbara touched many lives here in our community—even around the world, I learned later. Her quiet strength, support, and friendship will be missed. Her dedication to exercise was exemplary. She was a role model for how she gave of her time and talent to NAMI and The Other Door, to friends in need, and to me years ago when my neighbor Pat died.

In Barbara’s passing, we have lost a person of true grace and kindness. I'll bet she was warmly greeted by Pat. I can almost see them organizing, rallying for social justice, and sharing their concerns over the next presidency.

Our friend Barbara died the way she lived: peacefully.

There will be a service for Barbara on Thursday, February 22, at Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary Catholic Church in Viroqua. Visitation at 10 a.m. and a funeral Mass at 11 a.m.

Shocked!

“I like the mornings best, right after I wake up. I forget everything for a while and feel normal, like none of this has happened.”

I was at my desk, working on my lesson plans for that week's workouts, when Dane came down the stairs and told me this. One hand was carrying his book and water cup, and the other was clutching the shoulder strap that cradles the battery pack of his LifeVest.

Ever since he was released from the hospital, Dane’s been busy preparing for his next echocardiogram, which will determine how efficiently his heart is pumping blood (called the ejection fraction, or EF). So many things—being able to drive, to live on his own again, and to work—depend on an improved EF. The normal range is between 55 and 70 percent. On October 13 Dane’s EF was at 36, but after his heart attacks it dropped to 25. To get back to a normal lifestyle, he needs to get that number to 35.

The vest, designed to prevent death from sudden cardiac arrest, has been a necessary pain. The weight of the battery pack has caused his back to ache and has resulted in a forward posture he didn’t have before. It continually malfunctions, causing him additional stress.

Twice, LifeVest reps, one from Eau Claire and one from Madison, have come to the house on a weekend to switch out the vest with another because the alarm wouldn’t stop shrieking. If the alarm isn’t manually turned off within 25 seconds, it will alert bystanders to stand back, then emit a blue gel and shock him. On a recent warm-weather walk, the alarm went off six times in little over an hour, making the walk anything but enjoyable.

Often, Dane forgets he’s tethered to the vest and stands up, only to have the chair, where he hung the shoulder strap, tip over.

After breakfast and a shower, Dane meticulously dismantled his vest, removing all the wires and doodads, and washed it in the sink, then carefully laid out his second vest on the bed while he went to put the first one in the dryer. He attached and snapped the wires into place before putting the new one on.

When I finished class that morning, Dane walked in, clean and bare-chested, his arms raised over his head as if he were surrendering. “Can you look over the vest and see that everything is okay?” He turned slowly while I ran my hands under the vest and checked each electrode to ensure they were connecting with skin. I also made sure the wires hadn't inadvertently gotten crossed or come loose.

“You're all set,” I said. Then, noticing his thinness, I asked him about his weight.

“It’s 149.6. When I look in the mirror I see an old man’s body.”

Dane's COVID weight had gotten up to 180, but his preferred weight is 160.

“I’m sorry,” I empathized. “Remember to eat a few handfuls of your almonds.” Going below 160 wasn’t part of the plan.

Dane's recent lifestyle changes include rarely using a salt shaker and keeping his daily intake of salt under 2,000 mg; eating more fresh fruits and vegetables; cutting back on processed foods as well as sugar and flour; eating more chicken/fish/beans and far less red meat; and drinking his recommended two liters of water daily.

The cardiologist is insistent about fluid intake as well as daily weight and blood pressure checks. Periodically Dane reports those numbers to their office.

On Dane’s first day of rehab last fall, he performed a simple test of walking for six minutes while they monitored his heart. Dane labored at it, hunched over the top of his walker, the LifeVest cords dangling out the back of his shirt. Taking baby steps and gasping for breath, he walked 720 feet.

On January 31, his last day of rehab, he retook the test. He’d been working toward it, not only in his program at the hospital but by walking up the hill from my driveway to Highway SS almost every day. He also began an exercise class three times a week and has included a weekly two-mile hike. His hard work paid off, and in those six minutes he went 1,370 feet without a walker!

So on February 1, he was ready to ace his EF test—and more than ready to get that darn LifeVest off, drive again, go home, and start work in May!

The sun was shining, the snow melting, and our spirits soaring as we drove to Gundersen for his test. After the test, we celebrated with somewhat healthy salads at Burrachos, knowing it would be at least a week or more before the results came back.

But the hospital called the very next day. Three abnormalities were found in his heart structure, and his EF was 30—even lower than his first test.

Shocked, not by the LifeVest but by the test results, Dane told me, “I failed. The whole time I was being tested, I kept repeating 40, 40 percent. I was positive I’d at least be at 35 percent and get free of the vest, but hoped I would be at 40.”

Still catching my breath at the news, I reminded him he didn’t fail this test. He did everything right, and everything he did helped him mentally, spiritually, and physically over these past months.

Dane hasn’t failed, but his heart isn’t doing well.

End the Nightmare

Nightmares started plaguing me Tuesday night—something I haven't experienced since I left the Milwaukee area over 24 years ago. When Dane asked me about it, I assured him I’m okay, that it’s my subconscious dealing with the aftermath of the workshop.

******

It’s Tuesday morning, and I’m rushing into the conference room at the Vernon County Sheriff's Office. I'm brought up short by a row of blue uniforms stretching across the room like a tight rubber band. Backtracking a few steps, I slip into a chair upfront and exhale.

The free two-day workshop, “Investigating Domestic Violence: Upping Your Game with Current Best Practices,” is being offered to law enforcement personnel and other community collaborators. I’m present as one of 24 HEART (Help End Abuse Response Team) volunteers led by Janice Turben, coordinator, Vernon County Domestic Abuse Project. HEART volunteers provide support for victims of domestic violence in Vernon County. We’ll take turns being on call, and once a scene is secured, we’ll be there to support the victim.

The HEART project was spearheaded by a grant written by Susan Townsley, clinic director of Stonehouse Counseling. At our orientation meeting, Susan explained that she was seeing the same people again and again in her practice and wanted to end that vicious cycle—particularly because children who are raised with violence tend to become violent themselves.

On average, it takes seven incidents of abuse before someone leaves their abuser. Often the victim stays because they have nowhere else to go, have children and pets they fear for, have been isolated from family and friends, and have come to see the abuse as “normal.” And leaving doesn’t always mean safety.

Sheriff Roy Torgerson welcomes our group and thanks us for our time. He works closely with Janice and Susan to ensure the HEART program will run smoothly.

The Vernon County Sheriff's Office received 94 domestic violence calls in 2022 and 85 in 2023. But many domestic violence incidents go unreported because victims fear for their lives or are promised by the batterer that it will never happen again.

The agenda is jam-packed. An expert from Milwaukee describes the dynamics of domestic violence: power and control, escalation, cycle, impact on victim, and perspective and behavior.

We break into small groups to work through some case scenarios. My group includes Janice, another HEART volunteer, and four law officers. When the officers decide they can charge the hypothetical suspect with reckless driving, Janice challenges them: How? They confer with each other thoughtfully and include us in the process.

For me, this is the best part. I believe that when our law enforcement is involved with the community, good things will happen. Seeing blue uniforms and guns can trigger a sense of danger and anxiety. But these are good people, learning how to better take care of folks like you and me.

When the first day’s session ends, I sprint for my car. The subject is a tough one, and the presenters have shared real-life scenarios, pictures, and body cam videos to drive home the urgency of the topic.

That night, my bed feels dark and scary. Facts from the workshop spin through my head: the impact of trauma on memory, cognition, and behavior; why victims often recant; the importance of evidence-based investigations; collaborating for the victims' safety; and offender accountability... Then the nightmares begin. No matter how hard I fight, I can’t get free.

******

Wednesday morning, I head back to the sheriff's office for the conclusion of the workshop. I’m grateful to be learning from experienced women in this field, but also tired. This time, I don’t startle at the sea of blue when I walk into the room.

Officer Palmer, of La Farge, shares the terrifying statistics of police suicides. He reminds his team that they don’t need to be alone with the trauma of their jobs and urges them to reach out for help.

Then a survivor shares her story in a nonlinear, disorganized, bits-and-pieces way. We know from our training that this is common for victims. The importance of listening, not interrupting, and not judging or thinking of questions has hit home. The full room is deadly quiet.

This brave soul, at one time a manager at a major company, tells us about her coworker, confidant, and friend strangling her and days later coming back to kill her. She can’t see well out of her left eye even after numerous surgeries, and her right hand, which was all but severed, doesn’t have feeling. I notice she doesn’t mention receiving any mental health assistance.

The rest of the workshop covers legal risk factors for victims, stalking, more case scenarios, report writing, and recognizing and documenting signs of strangulation, which precedes 53% of domestic violence homicides.

The workshop ends with questions and many thanks to the presenters and the county for offering this opportunity. Driving home, I keep thinking how lucky we are to have this level of commitment to the people of our community.

******

Thursday morning, Janice emailed the volunteers from HEART a heartfelt thank you and an offer for debriefing. When I go out on a call, I’ll feel reassured that the officers and I will be working as allies.

My nightmares are temporary. Hopefully, by being more aware, we can end the living nightmare for domestic abuse victims and their families.

For more information about the HEART program, contact Janice Turben (jturben@fccnetwork.org). For more information about programs for victims and batterers, contact Susan Townsley at info@stonehousecares.com.

Thank you to Sheriff Roy Torgeson for the photos.

Home

“I’m already feeling sad,” Dane says, after packing an overnight bag to take to his house. “Yeah, me too,” I answer.

There’s a reason we don’t live together, we’ve always said and believed. Each of us values our alone time and always will. But since Dane’s heart attacks last fall, he’s been living with me.

A month before his heart challenges began, we became engaged. People were excited for us, and their first question was always, “Whose house will you live in?” Or they’d exclaim, “Wow, you two are going to live together!?”

“No!” we'd answer and quickly remind people, “We’re making a commitment to each other, not living together!”

Today, almost four months later, as we were walking up the hill with the pups, we talked about Dane’s upcoming test. They’ll measure his heart’s ejection fraction (EF), the percentage of blood ejected with each contraction, to see if there’s been an improvement. Because Dane's percentage has been low, he still needs to wear the heart monitor (LifeVest), which means he can’t drive. If he can’t drive, he can’t work. If he can’t drive or work, he needs to live with me until he can, so I can be his driver.

So here we are, living together, but today Dane is heading home to spend the evening at his house. He will reunite with his cats, Spike and Blake, build a fire, do a bit of cleaning, and take care of his chickens. I’m heading to La Crosse for errands, and in the morning I have a date with friends.

It wouldn’t have been an unusual scene for us four months ago, but now we’re both feeling melancholic knowing we won’t see each other tonight or in the morning.

“Do you have your phone?” I ask.

“Yes.”

“Is it turned on?”

“Yes.”

We load up the car and meander the crooked 11 miles to his place. On the way, Dane says, “When I come home tomorrow…” and we look at each other. I mention that the word home has become confusing, and he agrees. Technically, I’m driving him to his home and going back to mine.

Yesterday, I commented on how flawlessly it’s worked for us to live together, despite how small my place is. Dane doesn’t think it’s too small, but when we’re making dinner it looks more like an intimate dance. And we’re both glad to know it can work, in case someday one of us needs care again.

The other day I was coming out of the Snake Shed with a hunk of hay for the donkeys and yelped when I about stepped into Dane. We both laughed in shock, and I asked what the heck he was doing. “Looking at you,” he answered, and we cracked up again.

This isn’t uncommon. Not long ago, while madly typing, I felt something behind me and turned. Dane, of course. “What are you doing?!” I squealed, my heart racing.

“Just seeing what you’re doing.”

We’ve gotten good at normalizing the winter animal scene here together. Dane yells down the stairs: “Lorca’s under the bed, Merlin is in the cat tower, and Monkey's sleeping in the cat bed on top of the trunk.”

I yell back up the stairs: “Okay, Maurice is curled up on your chair, and Salvador is down here eating. I’ll go round up Rupert and be right up. Do you have Finn’s bone?”

“Yes, he already ate it and is waiting for the one you’ll bring him.”

Thirty minutes later: “I found Rupert, but now I need to let Ruben and Téte out again. Are you sleeping?”

“I was until you yelled up here.”

Rounding up six cats and three dogs, covering the birds, misting and feeding the snails, emptying the litter boxes, and refilling the water bowls and the cats’ food bowls takes at least 30 minutes—with the two of us tag-teaming, about 15. Before we even begin these nightly rituals, we’ve already put the ducks and geese into the Duck Hall, given water and fresh hay to the donkeys and goats, and made sure Louisa had her bedtime meal with three apples.

Today, after my errands in La Crosse, I come home, do chores alone, and call Dane.

“How’s it going?”

“Okay.”

“I miss you.”

“Yeah, I miss you too.

Everything and nothing has changed. My home has become Dane’s home, and his house is still his home. Together we remain committed to loving and caring for each other in the simple life we’ve created.

There is a reason we don’t live together... because we each have our own homes and we enjoy our independence. But that doesn’t lessen the love we share.

Three Homes

Sally & Jane enjoying a summer adventure date

Keith, my boss for 15 years, used to tell me that we have three homes: one where we live, one where we go to work, and the other where we go to get away. Decades later, I’m finding deeper value in that concept.

Back then, I was managing Keith’s multi-facility club. Work was relentless, and “getting away” meant sneaking off to a back court to play racquetball, jumping into an aerobics class, or hitting the weight room. I rarely saw my live-in home, except to sleep. My true home away from home was Whitnall Park, with well-trodden paths weaving through the woods and a lovely garden. But I hardly ever had time to visit. I’d look longingly at it as I drove by on the way to work and home.

What happens when your work becomes the place you go to get away?

Nowadays, I spend more time at home than usual. This past summer, I quit a 10-year job in Richland County, where I’d spent more time driving to appointments than with clients. The work with my clients was rewarding, but the drive time was exhausting.

So all summer, after leading a class on Zoom and taking the dogs for a walk, my afternoons were peaceful. I’d start by serving lunch to Maude, my eastern box turtle. I enjoyed filling her special rock with lots of healthy goodies, then sitting back in the red chair to watch her eat. She’d carefully claw aside the carrots, broccoli, cucumbers, and even strawberries, to get to her precious Oscar Meyer wiener bits and good ol’ bananas. Her best friend, Mr. V (a vole), would scurry out from a tiny hole, snatch a piece of carrot, and zip away, only to reappear after mere seconds. Was Mr. V swallowing those pieces whole, or perhaps taking them to Mrs. V and the kiddos?

When Maude finished, she’d saunter off at an astonishingly fast clip, heading for a weedy clump of grasses where she’d take a long, deep nap. This would be my cue to fetch my own lunch and carry it to the bistro table on the back deck. No sooner would I plop down than Hans and Vincent, the resident kid goats, would appear, looking for handouts and not a bit fussy over what I had to share. Eventually, slow-moving Peepers would join us, being the elder goat at age 11.

It sounds like an ideal home life, but here’s where it gets confusing. No longer working in Richland Center, and now teaching all my exercise classes from home, I’m once again pondering Keith's theory of three homes.

What happens when you work from your home?

As it turns out, people in Blue Zones (a word coined by Dan Buettner, who studies areas of the world in which people live exceptionally long lives) also realize the importance of the three-home concept. In Blue Zones, they have what they refer to as “third spaces”—what Keith was calling our third home—where they go to get away and socialize.

The look of third spaces varies depending on the country. In Loma Linda, California, they are churches; in Sardinia, Italy, wine at 5 p.m. creates the third space. In Singapore, one hospital isn’t just for patients. It was built to draw in the community with tai chi and Zumba classes, a health-oriented restaurant, and a 2.5-acre garden on the roof where volunteers grow organic herbs, fruits, and vegetables for patients and the public.

An important function of these third spaces is to combat loneliness and isolation. According to US Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy, loneliness is as bad for our well-being as smoking 15 cigarettes a day. He says it’s “more than just a bad feeling. It has real consequences for our mental and physical health. It increases our risk of depression, anxiety, and suicide. But social disconnection also raises the risk of heart disease and dementia and premature death on levels on par with smoking daily and even greater than the risks that we see associated with obesity.”

Social isolation is becoming a disease with serious health consequences. In a recent Gallup survey, 17 percent of American adults said they feel lonely, 24 percent of young adults answered the same, and 1 in 10 elderly said they are lonely too.

The idea of three homes—one where we live, one where we work, and the other where we go to get away with others (third spaces)—is an important concept Keith was schooling me on all those years ago.

After our recent dump of snow, I’m glad I work from home. If I were still driving all over the county, classes would have been canceled, as would my appointments in Richland Center. But, like everyone else, I need to be careful I don’t become too isolated.

My work life is fulfilling, and I never feel lonely when I can go out my back door and take Louisa an apple, the donkeys a carrot, or share my orange peels with the goats. But I’m also thankful for getting out on adventure dates with friends and all the wonderful events our communities offer.

Thanks to my boss’s musings four decades ago, and the Surgeon General’s recent warning, the importance of this third space has hit home for me. Maybe we all need to pay more attention to our third home and keep this third space open for our neighbors, young friends, and the elderly this winter.

One Word

On my right hand, on my crooked index finger, I wear two thin silver rings with words engraved on them.

After Dad died, when I was a single mother and Jessica was only four, life became more challenging. Dad had been solid, my cheerleader, my go-to person, the one who loved me most. During that hard time, the word faith became my one-word mantra. I wrote it on 3x5 index cards and kept them close by. That word pulled me out of a lot of ditches where I felt stuck, unsupported, or useless. It still does.

Although money was tight, when I found a booth at the Wisconsin State Fair where they engraved words on rings, I bought a ring with the word faith on it. Faith seemed a better choice for me than hope. I wanted to believe one hundred percent that things would get better, that Jessica would be healthy and happy, and that our lives would get easier. To me that would mean having a reliable car, a job that paid more than what childcare cost, and an apartment that was clean and safe.

When Jessica was almost a teen, I participated in a mini-triathlon (now called a sprint) in Peewaukee the day before applying for a job. It was raining during the race, making a downhill stretch difficult to navigate on bicycles. Many people decided to walk down instead of ride. Already toward the back of the pack, I gripped my handlebars, leaned forward, and stayed on track, surprising even myself when I reached the bottom still upright.

Gary, the gentleman at the front desk of the club where I was applying for the job, kept me talking. When I mentioned the Tri, he made a quick call, then sent me downstairs to meet Keith, one of the club’s owners. Turns out Keith had watched that event because he lived in the area. He liked the fact that I’d ridden my bike down the treacherous hill.

I worked at that club for the next 15 years, and during that time purchased another ring that said courage. I felt I needed to be more courageous. Men dominated the fitness field in those days; women weren't even supposed to sweat back then. (Jane Fonda was just starting to change that!) I’d already dropped out of college due to the stress of unaffordable childcare costs and cars that repeatedly broke down. I knew it would take courage to stay in the relatively new field of fitness for women.

Not everyone likes to make New Year's resolutions, but one-word mantras are different. Instead of trying to predict what we’ll do or not do in the new year, how about choosing one word, the way I chose faith and courage?

For example, focusing on the word peace day after day may bring some into our life, or better yet, to the world. Choosing the word peace could be a reminder to take a few deep breaths and slowly release any tension we’re holding.

Or listen. There’s a reason we have two ears and only one mouth. Listening to our friends, family, and clients before speaking is a crucial skill. Listening without forming an immediate response in our head is an art. Truly listening and then reflecting on what we hear acknowledges the other person’s feelings and can help clarify what we think we’re hearing.

Focus: Staying in the game and not racing ahead to the finish. Being aware of where our mind is, one step or one project at a time. Bettering our focus isn’t easy, but what would the new year look like if we did?

Choosing just one word as an intention for 2024 isn’t as overwhelming as a long list of things we want to accomplish, habits we want to change, or what we want to prioritize.

I still wear my rings with the words faith and courage, but I’m ready to add a new one. The choices seem limitless: unity, balance, freedom, abundance, serenity, gratitude, trust, joy, move, inspire . . .

Choosing one word is simpler than vowing to lose 50 pounds, save 50 dollars a week, or finish your first marathon.

Brave, imagine, compassion, grace, assert, explore, flow, heal, harmony, growth . . .